“Jordan, since you’re planning on pursuing nursing, why don’t you call Virtua Hospital to see if you could volunteer to see what it’s about?”

“I already did, Mom. Just to shadow as a high school student, they need pretty much everything from the middle name of dad’s childhood pediatrician to my American Airlines frequent flyer number.”

“Try calling the local hospice then. I saw signs that they're desperately looking for patient visitors.”

Huh? Hospice? What’s that? Is that short for hospital? Like the mini-mart convenience store version of a Level I trauma center? A grab ‘n go, drive-thru type of medical care similar to a CVS Minute Clinic where the overworked, baggy-eyed, 5-o’clock-shadowed, caffeine-crashed, nicotine-deprived, too-young-for-jowls-at-his-age Physician Assistant sits, pen-tapping the 25-minute remainder of his 12-hour shift, praying that no more patients last-minute him so he could soon collapse onto his chocolate leather La-Z-Boy and binge-watch the latest season of Family Karma with leftover General Tso’s and a cold one?

Well, my imagination of hospice was dead wrong (pun intended). My trusty Google search resulted in something I wasn’t expecting — key words such as “palliative,” “comfort care,” and “life-limiting disease” pulled up.

So hospice is where the terminally ill go to live out their final days. I don’t know if I want to do this! I’ve never seen anyone die before, let alone even know people who’d passed away! What would I do if I witnessed an elderly patient flatline? Or worse, how about watching someone’s beloved cystic fibrotic son take his final gasp of air through his fatigued, scarred lungs? And then tending to that grieving family — what would I even say? Would I be able to emotionally weight-lift this heaviness?

While psychologically hyperventilating, I realized I first needed to see what hospice was about. On my first day, I was tasked with assisting Mr. L, a retired wealthy business executive suffering from stage 4 prostate cancer. Mr. L had no one who’d visit, so the volunteer coordinator made sure that I spent my entire allotted time with him. I was hoping he wasn’t some smug, arrogant, colostomy bag of a human. I soon discovered that Mr. L was kind-hearted and honest, with the generosity of a loving grandfather.

Within a month, I had grown to adore Mr L and knew more about him than anyone else in the institution. We both looked forward to our time together and the 2 hours of banter we exchanged at each visit. I can tell his favorites: a medium-rare prime rib with A-1 sauce, The Philadelphia Eagles, a “sexy” 1968 Camaro”, 75% off Walmart clearance racks with the yellow and black stickers, and The Monkees (“even though they didn’t write their own music!”) His peeves: Brazilian butt lifts, the Vlasic pickle stork’s voice, Clay Aiken, the entire state of California, and any dude hanging a pair of testicles off the back of his pickup truck.

Can you see why I love this guy?

Although Mr. L taught me not to take myself so seriously, the wisdom I gained from Mr. L and from the hospice experience reminds me how too many people make the mistake of placing value on materials over memories:

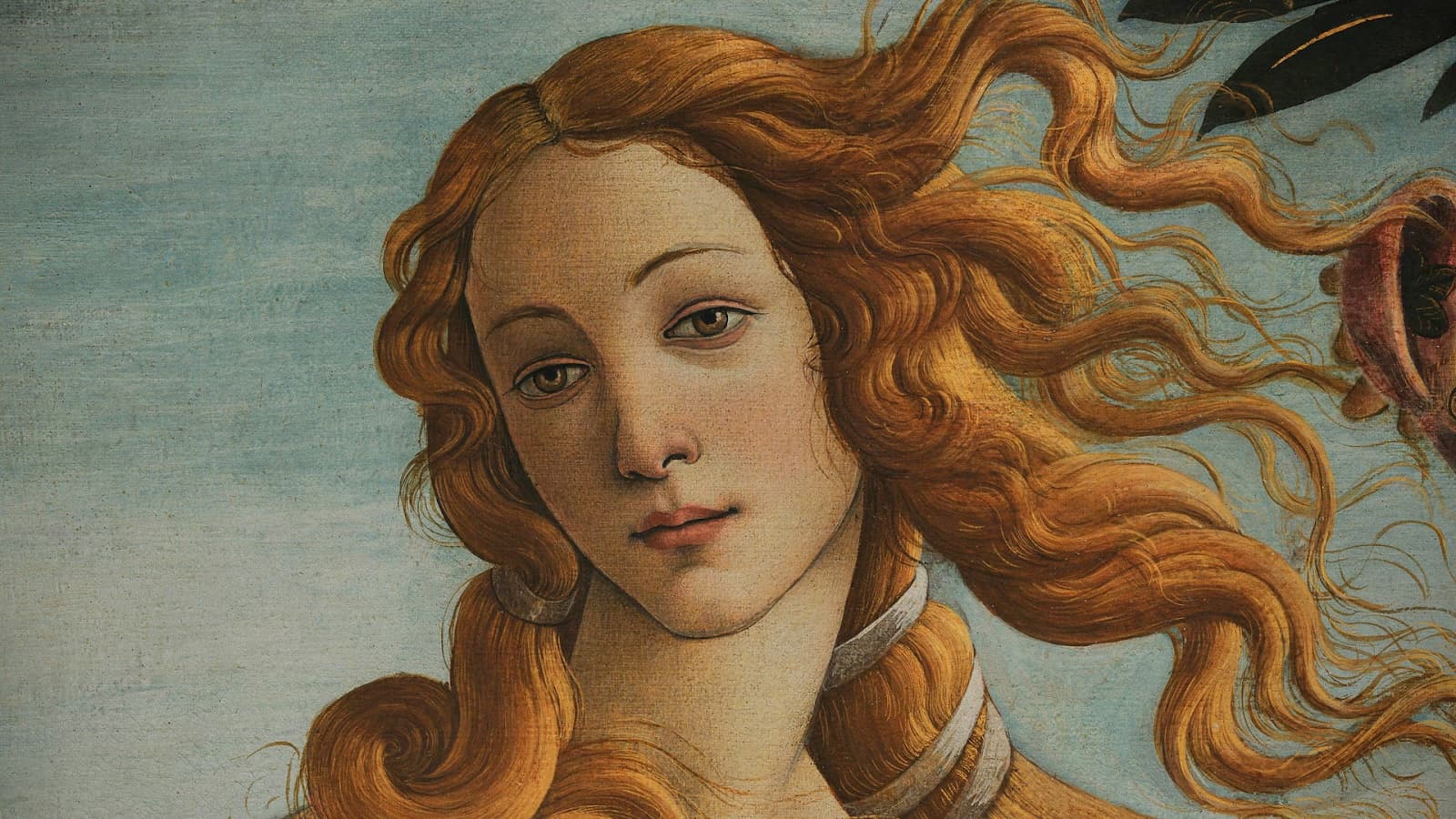

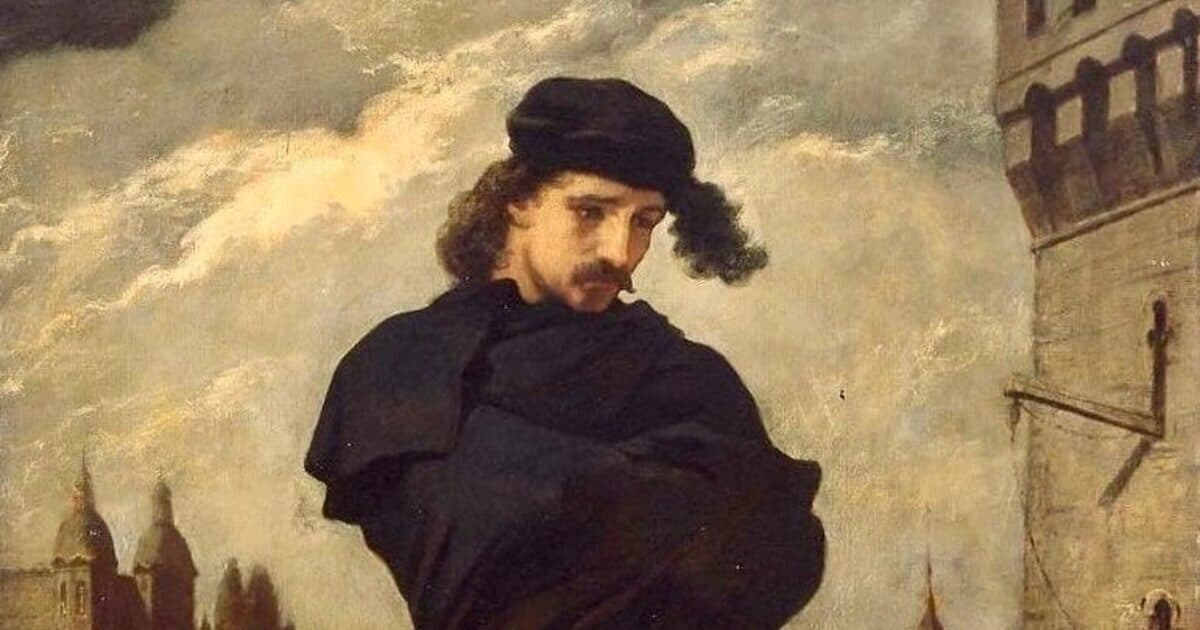

“When you're gone, son, nobody will think about your Rembrandt art collection, the luxury Moorestown, NJ digs for which you plunked down a cool $2.5 mil, or your 1961 Ferrari 250 GT California (OK, they'll probably remember that). My point is, my kids didn’t care about replaceable 'stuff.' I was so wrapped up with dining clients at Michelin star-rated restaurants and traveling internationally several times a month for decades that I neglected to be a present father to my own children. I thought I was being a solid provider and figured the boys would understand when they were older. But all they wanted was for me to play Parcheesi with them once in a while, attend their basketball practices, and teach them how to ride a bike, let alone drive a car. I’ve done none of that. I was always ‘too busy,’ and I barely even knew them. And now my life is a physical version of Harry Chapin’s best hit.”

Bro, who’s Harry Chapin?

After looking up the heartbreaking lyrics to Cat’s in the Cradle, it felt like my shredded pericardium and ventricular tissue within my chest required suturing. Talk about second-hand devastation. Generosity doesn’t simply refer to large cash transactions for your loved ones — it’s about making magic in the limited times you share together. I guess that's why our meetings brought Mr. L (and of course, me) such joy — they were deep, meaningful hippocampus souvenirs that could never be simply charged on a Visa.

"People assume that hospice means you can't walk, you can't talk, you can't eat, you can't clean yourself. I've been put out to pasture ever since my diagnosis. Retired, done, and deceased to all who knew me. Death has wait-listed me, and it’s only a matter of months before my number is called. But now I feel more alive than ever! I'm vivacious, and I have such a sunny outlook on life. I've embraced my diagnosis, and you keep me moving forward whenever you stop by. You have given me faith that even at this age, my greatest memory is yet to come! You've been like a grandson to… okay, enough of this sap. Grab me a fruit punch, will ya?"

Wow, I really have made a difference!

Mr. L and I have changed each others’ outlooks on life. I think I’ve shown him that you don’t need to be related to be family — loved ones aren’t always connected by DNA. And because of him, I’m reminded of my mortality, the importance of savoring each earthly millisecond, and having the courage to prioritize family over a job. I now understand that human connection can never be purchased.

Hospice nursing is my calling and will be my career. I’m looking forward to creating many more exciting moments with my patients, even if they’re their last.

Jordan Moham is a second-year nursing student at Rowan College in Burlington County, New Jersey

Discussion

Join the conversation! Login if you already have an account, or create an account. We would love to hear your perspective.

Comments

0Loading comments…